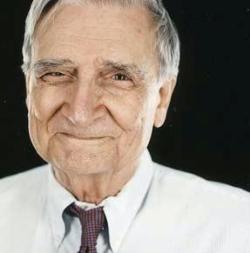

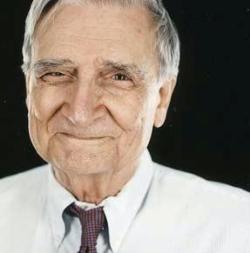

E O Wilson has a similar evolutionary viewpoint to Richard Dawkins but his tactics regarding working with Christians to save the planet seem diametrically opposed. Whilst Dawkins wants to do away with religion entirely, Wilson wants scientists to work with the religious to save the Creation - meaning biological diversity, ecosystems and species.

E O Wilson has a similar evolutionary viewpoint to Richard Dawkins but his tactics regarding working with Christians to save the planet seem diametrically opposed. Whilst Dawkins wants to do away with religion entirely, Wilson wants scientists to work with the religious to save the Creation - meaning biological diversity, ecosystems and species.

Listen: Podcast 1 | Podcast 2

From New Scientist September 30th 2006

Often cited as Darwin's true heir, E. O. Wilson has an audacious strategy for saving the planet: encourage evangelical Christians and scientific secularists to unite in caring for the ecosystems and biodiversity that he calls the Creation in his latest book. Ivan Semeniuk asked him if he has a prayer of succeeding when religious fundamentalism extends to the White House

After siding so strongly with science, you are now trying to reach across the science-religion divide. Why?

I offer the hand of friendship and I am presumptuous enough to do so on behalf of scientists - secular scientists. I feel that the time has come to put aside the culture wars, declare a truce and see if we can't meet on common ground where both sides can engage enthusiastically for our separate reasons.

What does the religious community offer?

There are 5000 members of 3 largest Humanist Organisations in the USA compared to 30 million members of the US National Association of Evangelicals. If only 1 per cent of those decide that they really would like to add conservation to the way they act out their religious beliefs in the world, that's 300,000 new conservationists. That's overwhelming.

The other reason is passion. Moral passion is what most evangelicals bring to the table. They believe, they care, and they really will work according to their beliefs. I think that having the living environment on their agenda for serious consideration and protection, with scientists playing the role of fact-gatherers and expositors of the problem, for example climate change or extinction of animal species, could be an extraordinarily strong combination.

Are you really optimistic that the religious community will listen?

I'm optimistic and getting more so all the time. When I made this move to approach the religious community and especially the huge block of evangelicals in this country, I was not aware of the extent of the greening movement that has begun at the political as well as the religious level. The political climate is favourable: there appears to be a mood growing to change the direction of the US. That, combined with the gradual greening that's occurring, leads me to be optimistic. And I'm particularly optimistic if, on the critical problem of saving the Creation - meaning biological diversity, ecosystems and species - we can combine science and religion, the two most powerful social forces in the world.

So what would you like to see happen?

A re-greening of America. I think the country is beginning to show a faint pastel green and I think it's growing greener every month. The phenomenal success of Al Gore's recent book and film about global warming, An Inconvenient Truth, is evidence that the American public is receptive to greening. And there is a mood already among many religious people that something has to be done about the environment. What's lacking is concern about the loss of the Creation. Why is that? Because people don't quite understand it yet. It's a more difficult concept to get your mind around.

Your book is written in the form of a letter or an appeal to a Southern Baptist pastor. Is that character someone familiar to you?

My "pastor" is abstracted from the Southern Baptist pastors I knew as a child. I grew up in the faith. As I like to say: "I answered the altar call and I went under the water." I can understand the culture very well, and in spite of the very stark, non-religious world view that I state upfront so as to put my cards on the table, I hope I come across as someone who is basically understanding, respectful and congenial in discussing subjects on common ground.

Having started out as a believer, how did you lose your faith and end up among the secularist scientists?

It happened to me in much the way that Darwin said it happened to him. He describes how he left England on the Beagle in 1831 as a devout Christian - I suppose now he would be called a fundamentalist - and then, in gradual degree, he pushed it away. He doesn't give specifics of what each of those little steps were, but you get the impression that most of it was unconscious, until finally he was a secularist. That's what happened to me in my teens. I didn't really have a knock-down drag-out fight with a fundamentalist parent or pastor. I just drifted away.

Is the spiritual approach to nature a conscious effort to speak the same language as the religious community?

I feel inside every word of that book. I do have a feeling that the spiritual side of the understanding of the Creation is powerfully ingrained - at least the potential is powerfully ingrained. Most of the scientists I know who actually work on biodiversity and conservation share that feeling. You can hear it in their voices. It's a powerful motivating force. Spirituality in this case does not mean religiosity. The great majority of scientists, I suspect, are secular. Yet they speak, when you get down to bedrock, in what you would call spiritual terms.

If the love of nature is innate, why is nature in such crisis and why is it so difficult to communicate the importance of conservation?

You've put your finger on it. There appears to be a hierarchy of drives in humans. The biggest concern is always survival and reproduction, and protection of clan and family. For most of human history, humans have had to struggle against nature to survive. Then with the Neolithic revolution we learned how to break nature by cultivating plants, clearing land and building surpluses of resources and developing technologies. But along the way, there has been this deep connection to having a natural environment, even if it's just to exploit it.

It took a few thousand years of adoring gardens, loving exploring, expanding into unspoilt environments and so on to bring us up short with the recognition that we've gone too far. We broke nature and now we're smashing it and getting rid of humanity's biggest heritage.

A sceptical religious leader might say that science and technology helped us destroy nature, so they should get us out of this mess.

Yes, they should. Science and technology combined with Palaeolithic obstinacy have brought us to this point. Now science and technology combined with a determination to save this world for future generations and a morality broadened to include saving the Creation has to get us out.

What about the evangelicals who argue that the world is coming to an end and therefore doesn't need saving?

The extremists among the evangelical community really do see the world as just a way station from which humanity is destined to ascend to heavenly bliss (the Rapture) or to remain and eventually go to hell. The movement that has taken that line is called the Dispensational movement, and I'm sorry to say it's quite strong in the US.

So who are they?

Dispensationalists believe that the Rapture will come in their lifetime or even any day now, in which those saved by redemption through Jesus will go bodily to heaven. All this is in the Book of Revelation, which is interpreted literally by the Dispensationalists to mean that the condition of the world is of little concern - that in fact, the sooner it deteriorates the sooner comes the Rapture.

The evangelicals that I've spoken with, including significant leaders in the evangelical movement, do not agree with that. I'm hopeful that while there are millions of Dispensationalists, nonetheless they will stay a relatively small fraction of the religious community.

How would you answer a religious leader who says scientists should give a little ground on teaching intelligent design so that young people better appreciate the Creation and lead the flock toward a greener future?

I would say that compromise and trading over world views and fundamental beliefs is not what I want to talk about, nor what I think would lead to any productive result. I'm interested in finding common ground that we can form an alliance on.

But suppose you had to answer.

OK. Let me say that it would be very much against the interests of organised religion to press the matter. Scientists agree almost unanimously that intelligent design is not science because it is based on a proposition which has negative evidence. Because scientists have not yet solved all complex systems, especially biological ones, believers in intelligent design say that you have to turn to another explanation which can only be supernatural.

The opposition to this is not a conspiracy of scientists who want to keep religion out - quite the contrary. The currency of science, its silver and its gold, is discovery. You are a scientist if you make original discoveries. You are a success if you make important discoveries. So they're not in any conspiracy, they just won't accept what they would consider worse than bad science - non-science.

What's your advice for adults who want to instil a love of nature in children?

Early exposure in pleasant circumstances is the best way to make a naturalist. Take a child into the field and encourage him or her to become an explorer, adventurer and treasure hunter in the environment. Little children are savages, they are Palaeolithic creatures with a strong desire to explore on their own or in small groups. It's well established that between the ages of 9 and 12 children have an innate desire to build tree houses or little retreats where they can be on their own - preferably in the woods if they have access to them.

They should also be turned loose in places where they can bring back a frog or a snake or spider in a jar. With that kind of experience you can make a lifelong naturalist and build a culture that doesn't turn away from modern technology and the accoutrements of western civilisation, but one that enriches it by adding a love of nature.

From issue 2571 of New Scientist magazine, 30 September 2006, page 54-56

Profile

Edward Osborne Wilson's love of nature developed as a child in the countryside around Mobile, Alabama. He became passionate about insects, especially flies. A shortage of insect pins during the second world war led him to switch from flies to ants, which could be stored in vials. He graduated from the University of Alabama, going on to a PhD in entomology at Harvard University. He caused a furore in 1975 with Sociobiology, which was vilified by various groups as the "new eugenics". Among his other well-known works are Biophilia, The Ants (with Bert Hölldobler) and Consilience. His latest book, The Creation, is published by W. W. Norton